By making effective base models, you can greatly decrease redundancy and wasted time during production. Those who are familiar with video game design also know that it allows for the same rigging to be used for multiple models. I find it interesting that rigging seems to be absent from 3d miniature design, but more on that later.

So, what are base models and how can they be designed effectively?

Lets tackle the first question. A base model is simply a boiled down and very basic version of the final product. It has no outstanding details, but should convey a general feeling of what it is, be it a car, gun, human, house, etc. Remember that it still needs to have defining features, just not specific to an individual model.

Here is an example:

This is obviously a human male, but it doesn't contain any specific features. This could potentially be anyone.

Now how do we make effective base models? Remember, a base model is meant to save you time and reduce your work load. This means that you will need to focus on two points:

A) How will this model be used in the future? (basic geometry)

B) What features will be common among all the models? (details)

Question A is for the basic geometry. Say you're making an assault rifle, as an example. You might say that all rifles have a grip, a trigger, a charging handle, a barrel, and a magazine. So basic geometry should reflect all of these, right? Not quite. This is where you must evaluate your future designs that will be based on this model. If you are going to make a bullpup configuration, a conventional magazine well would then need to be moved:

In the above image, we see two rifles. The top rifle is a bullpup with its magazine behind the grip. The bottom is a conventional rifle with the magazine in front of the grip. Those of you who don't study firearms might be thinking "So what, just move the box back and call it good!" That's great if you're making low poly models for an RTS, but people want more detail in their miniatures.

If you move the magazine back, you also have to move bolt, and ejection port back, increase the size of the stock, and change the hand guard. Generally you'll need to shorten the barrel as well. So now you're doing a lot of work to retool a base model to fit the same item type. This is also true for organic models, cars, airplanes and everything else. You don't try to make an F15 fighter out of a cargo or biplane base.

So, you'll need to consider what you're finished product will be. Are you going to make 30 or 40 assault rifle variations? Get pictures of each weapon and sort them into groups by common features. A quick breakdown can give us:

- Handguns

- Semi-Automatic

- Revolver

- Assault Rifle

- Standard

- Bullpup

- Rifles

- Bolt Action

- Automatic

So you see how this can break down into a lot of base models! This isn't necessarily a bad thing if you have a full art team, as some people will be making base models while others add detailing and finalize them. It can be a bit much for one person though, so it's a good idea to prioritize your models. Use just a single type until you've completed your goal, then branch out as you have time. Using the assault rifle example, you should pick only a couple types of weapons to begin with, such as semi-automatic pistol, standard assault rifle, and pump action shotgun. This gives you three base models to work with and keeps the scope of your project much more reasonable.

Once you've narrowed down your base models and their basic geometry, you can move on to the second point. Given a single base model, what will all of the final models have in common? It is important to compare each model and determine what similarities there will be between them. For example, all of your semi-automatic handguns may have recoil operated slides and round trigger guards. This is a detail specific to automatic pistols, but not other weapons.

For example:

You'll notice that, despite color, size, and model, each one of these handguns have striking similarities, especially when contrasted with revolvers. So the question is, why redesign the slide for each weapon? For miniature games (especially 15mm) these details need not be very specific or varied. You can replicate these subtle details over many weapons without the design becoming boring.

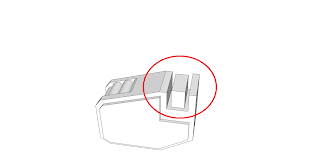

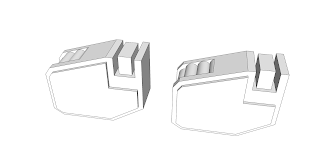

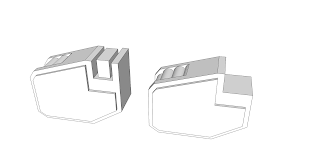

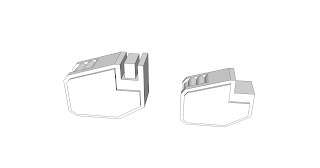

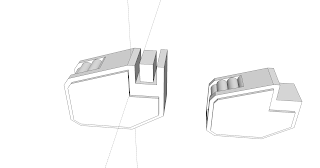

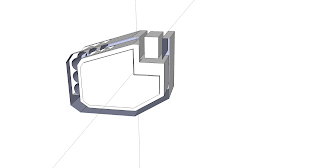

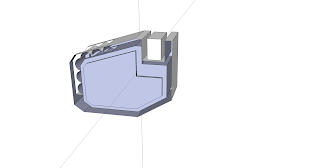

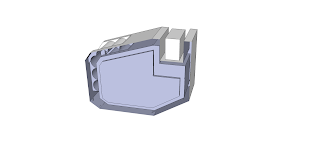

Consider the following example:

This is the base model I made of a Warhammer 40,000 bolter. I knew that if I made any alterations, they would not be with the charging handle, magazine well or grip (actually, its a specifically designed flat area, as space marine hands have the weapon grip molded into them. You just have to make certain to design the weapon to properly fit over the hand). I decided to extend out the barrel and add an integrated, bottom fed grenade launcher.

Notice how I was able to simply extend the front and model the grenade launcher? I didn't need to change any of the subtle details (though I did decide to take off the front sight aperture, as I felt it was redundant with a holographic sight). I then decided to completely break away from this concept. Using the same base model, I shortened the barrel length and added option "lock in" parts:

95% of the details on the bolter remained the same, with only a minor reconfiguration of the foregrip and bottom mount for combi-weapons.

Now, obviously you can decide to get crazy with your designs and make everything completely unique. It might even sound very good on paper. However, I have to advise against this. You're severely limiting your output and variety of models, plus you're reinventing the wheel with each model. Even if you don't specifically intend to produce multiple models or kits, making a base model can allow you to revisit designs or start over if you don't like the end result.

Even more important, if your clients like the work and want derivatives, you don't have to start over or dramatically alter the finished product. You'll have a large portion of the work already completed. You can then offer a discount on the work, or seriously cash in on an easy project (though you'll get more return work going the discount route).

As always, I hope this helps an thanks for reading!